We all want a long, healthy life. These two things however don’t always go together. As life gets longer, if it does, health becomes harder to retain. This is the struggle between lifespan and healthspan. Given a choice, of course, we all want as much as possible of both. It is of little use, after all, to have a long life if we can’t enjoy it, have little physical control over our own body and need medical attention all the time.

This is where muscle strength comes in. Dynapenia[1] is the medical term for the age-related loss of muscle strength human bodies experience as they get older. As muscle strength is lost it impacts negatively on mobility, sense of personal freedom and the ability to control our body. Sarcopenia[2] is the age-related loss of muscle mass which leads to progressive loss of strength, function and mobility in humans as they age.

It would appear that left to their own devices human bodies are destined to lose muscle mass with age and lose strength in the muscles they do retain, making them even weaker. None of this is good news. But there is no problem without a solution.

Sarcopenia, the tendency to lose muscle as we age can be successfully resisted with resistance exercises.[3] By lifting weights, and using bodyweight exercises that force muscles to stretch and contract (think push-ups, squats, chin-ups and sit-ups) we force the body to trigger its adaptive response to persistent external stressors and force muscles to grow and get stronger.

Muscles Contribute To Cardiovascular Fitness

We need strong muscles not just to get about and feel in control of our body and life, but also to maintain our health as we age. A ten-year-long study[4] involving both men and women in Athens, Greece, showed that cardiovascular health and freedom from heart disease as we age is directly linked to muscle mass and muscle strength.

Muscles are energetically expensive for the body to build and maintain. They place an extra load on the heart and lungs which means these organs get a heavier workout and remain, themselves, fitter if we have stronger, larger muscles as we age.

Strong muscles don’t just help our cardiovascular system, they also help our bones remain stronger and healthier and our bones, in turn, affect how strong and healthy our brain is.

Muscles Help Us Retain Youthfulness

We already know that after the age of 60 the body’s metabolism undergoes substantial changes that affect our overall health and fitness. Losing muscle mass and muscle strength is one aspect of this which is why it is so important to focus on building strength and muscle as we age. A UCLA study[5] focused on older adults found that after the age of 60 “an average male who weights 180 pounds might after age 60 lose as much as 10 pounds of muscle mass over a decade.”

That’s muscle that would keep the heart and lungs strong and our bones and brain healthy. Losing it is what ages us biologically. Suddenly our cardiovascular fitness is no longer what it used to be. The basic functionality and mobility of our body is impaired. Our mental clarity is compromised.

Taking active steps to build muscle through sustained, daily resistance exercise helps keep the aging effects at bay. Improved cardiovascular fitness prolongs our lifespan. Being able to retain our independence and function as strong, healthy adults prolongs our healthspan.

A meta-analysis[6] of studies that examined the link between exercise in older adults and loss of muscle mass due to ageing, later in life, showed that building up muscle mass and muscle strength, earlier in life can help stave off the effects of ageing.

In addition, strength training helps retain mobility and basic physical function as we age[7] and, according to a 15-year-long cohort study in the U.S. it helps increase our lifespan.[8] The increase in lifespan and healthspan is attributed to more than just the ability to feel strong and keep active. Muscles are emerging as the body’s largest secretory organ[9]. They’re actively engaged in the creation of a number of neurotransmitters and other hormones that enable them to communicate with many other organs in the body.

A loss of muscle mass due to general inactivity impairs the inter-organ communication that normally takes place in a healthy, younger body and presents the opportunity for health complications to take place.

While we may need more strength training as get older[10] to remain strong and healthy, the good news is that a sustained routine of daily exercise can keep us feeling younger, stronger and healthier for most of our lives.

Summary

Strong, healthy muscles help us:

- Feel independent and be mobile on our own.

- Maintain bone and brain health and keep dementia at bay, as we age.

- Keep our hart and lungs and overall circulatory system functioning properly.

- Prolong our lifespan through a complex interaction of physical activity and secretory work.

- Prolong our healthspan by maintaining the body’s biological age even as chronologically we accumulate time.

We can get strong again at any age but in order for that to happen we need to be smart: a sustained, sustainable daily routine is necessary. Adequate sleep and food are also key ingredients of every long-term plan to maintain strong, functioning muscles that help us feel younger in our body and mind even as the calendar years accumulate.

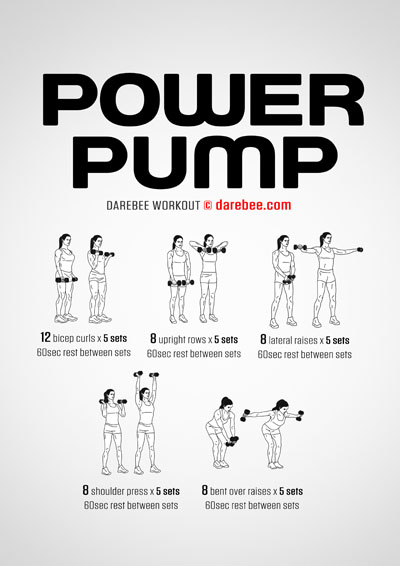

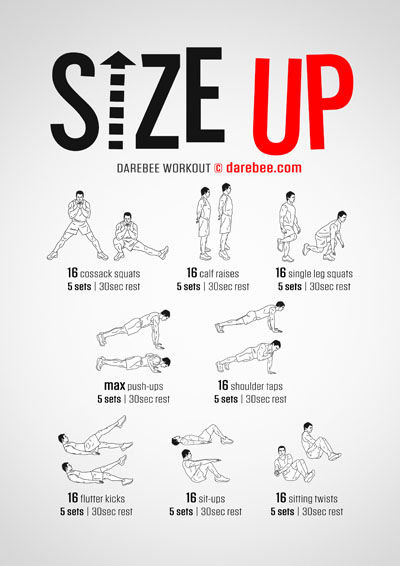

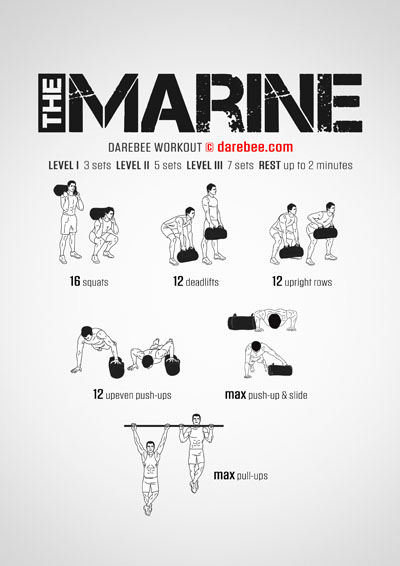

Recommended workouts:

Check out our database for almost 1,000 strength workouts for every fitness level and age group.

References

- Clark BC, Manini TM. What is dynapenia? Nutrition. 2012 May;28(5):495-503. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.12.002. PMID: 22469110; PMCID: PMC3571692.

- Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, Paoloni M. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2014 Sep;11(3):177-80. PMID: 25568649; PMCID: PMC4269139.

- Law TD, Clark LA, Clark BC. Resistance Exercise to Prevent and Manage Sarcopenia and Dynapenia. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;36(1):205-228. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.36.205. PMID: 27134329; PMCID: PMC4849483.

- Tyrovolas S, Panagiotakos D, Georgousopoulou E, et al. Skeletal muscle mass in relation to 10 year cardiovascular disease incidence among middle aged and older adults: the ATTICA study J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:26-31.

- Muscle Mass Index As a Predictor of Longevity in Older Adults. Preethi Srikanthan, MD, MS Arun S. Karlamangla, MD, PhD. Published:February 20, 2014DOI.

- Steffl M, Bohannon RW, Sontakova L, Tufano JJ, Shiells K, Holmerova I. Relationship between sarcopenia and physical activity in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017 May 17;12:835-845. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S132940. PMID: 28553092; PMCID: PMC5441519.

- Billot M, Calvani R, Urtamo A, Sánchez-Sánchez JL, Ciccolari-Micaldi C, Chang M, Roller-Wirnsberger R, Wirnsberger G, Sinclair A, Vaquero-Pinto N, Jyväkorpi S, Öhman H, Strandberg T, Schols JMGA, Schols AMWJ, Smeets N, Topinkova E, Michalkova H, Bonfigli AR, Lattanzio F, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Coelho-Júnior H, Broccatelli M, D'Elia ME, Biscotti D, Marzetti E, Freiberger E. Preserving Mobility in Older Adults with Physical Frailty and Sarcopenia: Opportunities, Challenges, and Recommendations for Physical Activity Interventions. Clin Interv Aging. 2020 Sep 16;15:1675-1690. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S253535. PMID: 32982201; PMCID: PMC7508031.

- Jennifer L. Kraschnewski, Christopher N. Sciamanna, Jennifer M. Poger, Liza S. Rovniak, Erik B. Lehman, Amanda B. Cooper, Noel H. Ballentine, Joseph T. Ciccolo, Is strength training associated with mortality benefits? A 15 year cohort study of US older adults, Preventive Medicine, Volume 87, 2016, Pages 121-127, ISSN 0091-7435,.

- Pedersen BK. Muscle as a secretory organ. Compr Physiol. 2013 Jul;3(3):1337-62. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120033. PMID: 23897689.

- Mayer F, Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Carlsohn A, Cassel M, Müller S, Scharhag J. The intensity and effects of strength training in the elderly. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 May;108(21):359-64. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0359. Epub 2011 May 27. PMID: 21691559; PMCID: PMC3117172.