If you’ve trained with a group of people at any time, or even trained with a partner you intuitively know this to be true: you perform better when you train with others than when you train on your own.

On paper this, at first, makes little sense. After all we train on our own because we get to completely control the environment and its variables. In the seclusion of our own home we don’t have to worry about being judged on the way we look or sound as we push ourselves beyond our comfort zone. Nor do we have to face the fear of failure in front of others.

Self-Determination Theory[1] that explains our motivation to develop skills and abilities which we can then use to our advantage in broader, more competitive contexts explains this in a more scientific way.

While all of this is true we are, however, truly complex beings that have evolved to closely interact with others and to be motivated by many different things. The social aspect of our nature has an inevitable effect on our performance that studies have shown can be either positive or negative. Psychologists call this phenomenon Social Facilitation[2] and, as a theory, it first came to attention in 1898 when Norman Triplett noticed that cyclists that trained alone performed worse than their teammates who trained in a group. In 1920, psychologist Floyd Allport gave it its current name.

Since then we’ve had a large number of experimental studies that have not only analysed the components of Social Facilitation but also explain, in part, how specific emotional and cognitive states affect the way our body behaves.

What Happens If We Exercise With Others?

When we exercise with others, even if the person we are co-exercising with is our romantic partner we either do better than when we exercise alone or we do worse.

Psychologists call this effect Social Facilitation (when we do better) and Social Inhibition (when we do worse). Social Facilitation, that improves our performance, in turn is divided into two distinct components called the Co-Action Effect and the Audience Effect. Basically, when we exercise with others who are performing similar physical tasks to our own (co-action) our performance improves even if there is a competitive element to what we do.[3]

Similarly, when we have an audience and we perform a physical task we have performed before and feel competent about, our performance also improves.[4] However, when the task we face is new to us, complicated and we don’t have confidence in our ability to perform well, then the presence of an audience, even a very small one, has negative impact on us and we perform worse than if we performed alone.

The reason our performance is affected in each of these situations is explained through Arousal Theory.[5] Basically, the presence of others excites, activates the higher centers of our brain, raises our blood temperature and can increase our heartbeat. A lot of complex neurochemical messaging takes place and a certain amount of inner mental modelling but essentially it all comes down to this: When the task we perform is something we feel we are good at this arousal allows us to channel our physical and mental resources to what we do and do it better.

If, however, the task we perform is new to us or we lack confidence in our own ability the arousal we experience also increases our level of anxiety. Cortisol, the stress hormone, accumulates in our bloodstream and that interferes with our ability to concentrate and perform tasks. So our physical and mental performance drops in quality.

How To Best Exercise With Others

If exercising with others can be better for us than just exercising alone how do we make sure that when we do exercise with others it works in our favor instead of activating Social Inhibition and holding us back?

Neuroscientific studies[6] show that the parts of the brain responsible for making the experience of exercising with a partner positive or negative involve the activation of the brain’s reward system. This helps us come up with a set of guidelines that will help you exercise with a friend or a romantic partner and physically benefit every time.

- Decide what you’ll do and establish the rules of ‘competition’ (if any).

- Make it fun from the very beginning. If there’s no enjoyment to start with it’s unlikely to get any better as the physical going gets hard.

- Determine why you’re working out together. If you’re afraid you’ll be judged the moment you make a mistake or start to look sweaty and tired then you’re unlikely to truly enjoy working out with someone else.

- If it’s going to be physically hard accept before you start that messing up, getting tired, failing to fully perform some exercise is OK.

- Make the fact that you’re working out with someone be more important than the need to look good while you’re working out.

- Make it as social as possible. Just because you’re working out doesn’t have to be like a Boot Camp atmosphere. Social banter, jokes, conversation and socializing has to be just as central to your working out with a friend or romantic partner as the physical exercises.

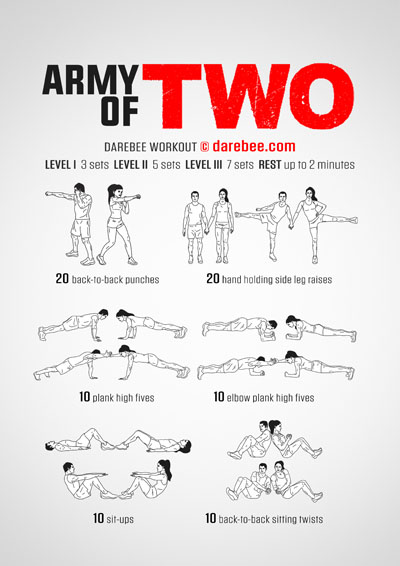

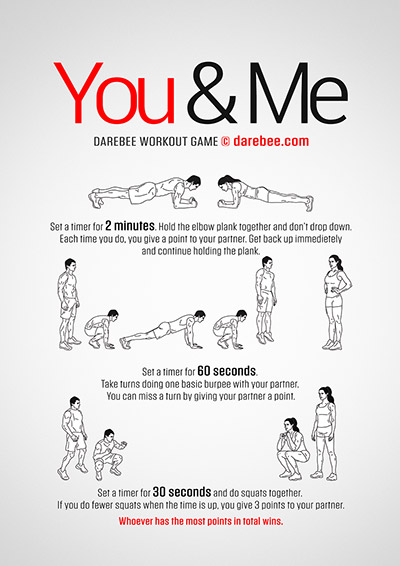

Workout Ideas

References

- Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Ryan RM. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:78. Published 2012 Jun 22. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

- Guerin, Bernard. (2009). Social Facilitation. 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0890.

- Lugo, Ric & Thomas, Sion & Channon, Alex. (2018). The Influence of Competitive Co-Action on Kata Performance. Martial Arts Studies. 5. 10.18573/mas.49.

- Hamilton AFC, Lind F. Audience effects: what can they tell us about social neuroscience, theory of mind and autism?. Cult Brain. 2016;4(2):159-177. doi:10.1007/s40167-016-0044-5

- Matthews, Gerald & Amelang, Manfred. (1993). Extraversion, arousal theory and performance: A study of individual differences in the EEG. Personality and Individual Differences - PERS INDIV DIFFER. 14. 347-363. 10.1016/0191-8869(93)90133-N.

- Vikram S Chib, Ryo Adachi, John P O’Doherty, Neural substrates of social facilitation effects on incentive-based performance, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 13, Issue 4, April 2018, Pages 391–403.