Stretching is one of the most misunderstood activities in fitness. Because it is mostly associated with the “bend down and touch your toes” variety of exercise its importance is frequently overlooked and the benefits it can provide are lost.

As muscles grow and as they age, they change. A balanced stretching routine helps provide more even muscle growth along muscle fibers and an increased degree of flexibility, both of which provide a fuller range of motion, greater freedom to move our body as we wish and provide us with more power when we ask it to do something.

In addition to this stretching also helps achieve:

- Increased flexibility in the joints

- Better circulation to the muscles and joints being stretched

- Increased energy levels (as better circulation brings in more oxygen and glycogen)

- Better coordinated movements

- Increased speed and power

There are seven different types of stretching and although some overlap and some you will probably do a little of as part of your training anyway, it’s good to take a closer look at and what they do.

Active Stretching

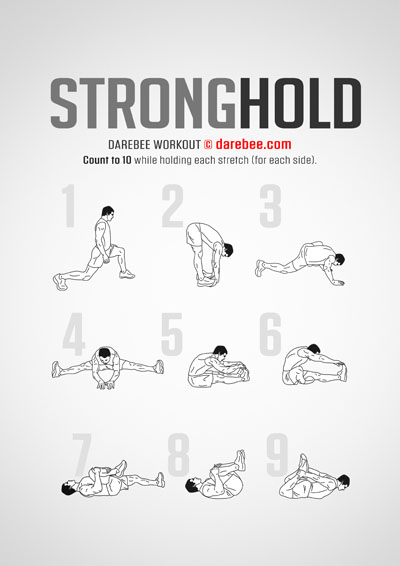

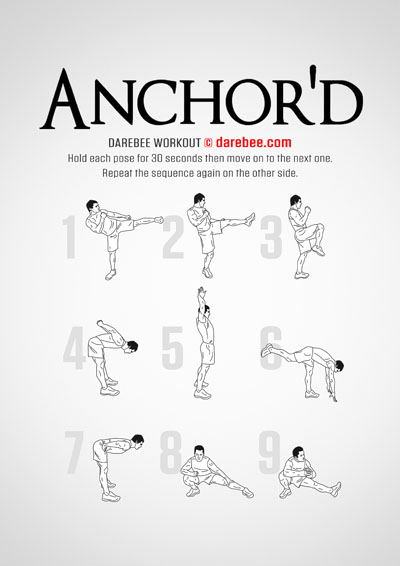

In active stretching you assume a position and hold it without any assistance other than that of the agonist (primary) muscles involved in that position. In order to hold the body in a particular position the agonist muscle groups need to tense which means that the antagonist ones begin to stretch. Holding a martial arts side kick position, for example, helps stretch the adductors and increases flexibility and kicking height for the martial artist.

Active stretching works because of a physical response called reciprocal inhibition where when one muscle group is tensed and held in position for a prolonged period of time the muscle group opposing it relaxes as there is no need for it to remain tense, and is therefore elongated. You don’t need to hold active stretching longer than 30 seconds at the most and in many cases it begins to deliver results in shorter time intervals of 10 – 15 seconds.

Yoga, in particular, uses active stretching quite a lot. Martial artists and ballet dancers also make heavy use of it. Most sports can benefit from active stretching techniques.

Passive Stretching

Passive stretching is an ideal form of stretching to perform with a partner. It requires the body to remain completely passive while an outside force is exerted upon it (by a partner). When used without a partner bodyweight and the force of gravity are allowed to do their thing. Passive stretching is also called relaxed stretching, for that reason.

Doing the splits is one perfect example of passive stretching. By placing your feet as far apart as possible and simply resting your bodyweight on your hips you slowly allow your legs to slide further and further apart naturally. Because passive stretching happens gradually and it requires some time in each position studies show it is ideal for rehabilitating muscles after an injury.

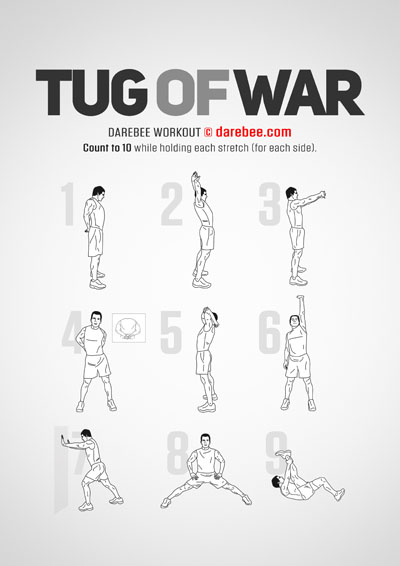

Static Stretching

Static stretching is probably the most common form of stretching and it requires a stretch to be held in a challenging but comfortable position for anywhere between ten and 20 seconds. Because it doesn’t push the body to stretch to any extremes it is frequently used as part of the warm-up routine in sports. This has led to the misconception that stretching is required in the warm up in order to prevent sports injuries and that stretching enhances sports performance.

In 2013 three independent studies looked at this from different perspectives. One, published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports found that static stretching carried out as part of the warm up routine contributed to a decrease in muscular performance and introduced instabilities in the muscles which may also contribute to more injuries occurring, instead of less.

The second study published in the Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research found that static stretching carried out as part of the warm-up routine contributed to an immediate decrease in muscular performance. This was further backed up by the third study published in the same journal that found that long-term benefits of pre-workout static stretching were negligible at best.

Isometric Stretching

Isometric stretching is a type of stretching that involves the resistance of muscle groups through isometric contractions (tensing) of the stretched muscles. Pushing against a wall to stretch your calves, putting your leg, straight on a bar and pulling your head down towards your knee and stretching your bicep by putting a straight arm against a wall and exerting force against it are all common examples of isometric stretching.

Because isometric stretching involves a measure of resistance there is some evidence that it helps develop muscle hypertrophy (increased muscle size) when carried out over a prolonged period of time.

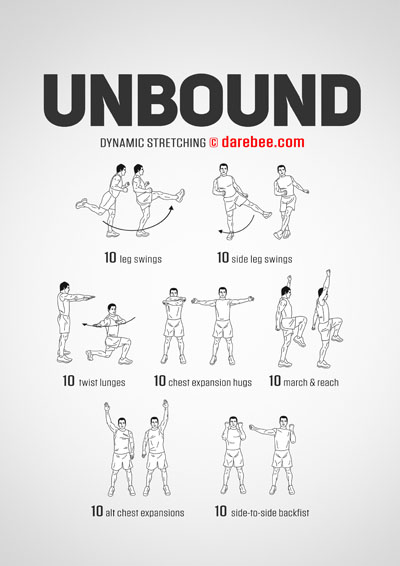

Dynamic Stretching

Dynamic stretching uses gentle swings to take the body and its limbs through their range of motion. Because the speed at which dynamic stretches are performed is gradual and the range of movement is within the comfort zone, dynamic stretching is one of the most highly recommended stretching routines that can be carried out as a warm-up.

Golfers, boxers, martial artists and ballerinas routinely use dynamic stretching as part of their preparation routine for high intensity activity. A 2011 study published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology found that dynamic stretching provided increased performance for sprinters and athletes involved in high intensity activity.

A further, independent study, published in 2012 in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine compared the benefits of dynamic versus static stretching for high intensity athletes and found that those who used only dynamic stretching in their warm up performed better than those who uses static stretching routines. However, those who combined both had a better range of movement (ROM0 overall, suggesting that a mixed routine could deliver superior results.

Ballistic Stretching

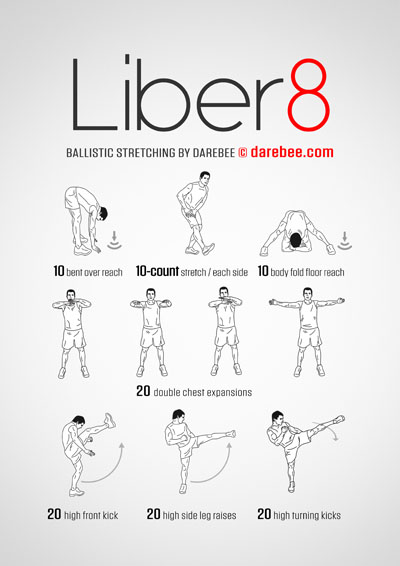

Ballistic stretching is a form of stretching that uses bounce and muscle explosion to force a stretch through a range of movement or a fixed position. This is probably the one type of stretching that’s got the worst rap from the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons who frequently cite it as one of the most common causes of injuries suffered during warm up and stretching routines.

Because ballistic stretching pushes the body beyond its comfort zone it should never be tried without an adequate warm-up. This warning also suggests that to use it as a warm-up is contra-indicatory. Ballistic stretching is routinely used by (properly warmed-up) martial artists, ballet dancers and gymnasts to take the body part its comfortable range of motion and achieve flexibility and range of motion gains.

Studies on ballistic stretching show that when performed post-workout or as standalone workouts it can provide greater benefits in the range of movement and contribute to better performance, something that martial artists, gymnasts and dancers know only too well.

PNF Stretching

PNF stretching which is also known as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching, is a set of stretching techniques that can increase both active and passive range of motion and provide real gains in flexibility.

A study published in the Animal Science Journal found that stretching (which includes PNF) can activate the muscle building pathways leading to increased strength and muscle size as long as the stretching is performed after high intensity exercise.

When it comes to stretch routines PNF is probably the king of stretches using resistance against an applied force, followed by relaxation and a repetition of the stretch to achieve rapid gains in flexibility, joint strength by eliciting four separate, sometimes overlapping responses: autogenic inhibition, reciprocal inhibition, stress relaxation, and the gate control theory. All of these are explained in detail in a study on PNF benefits published in the Journal of Human Kinetics.

When Should Stretching Take Place?

If you are using stretching in your pre-workout warm-up routine you should use either Dynamic stretching or PNF, otherwise all stretching should happen post-workout, when the muscles are thoroughly warmed up or it should be a workout all of its own (on a separate day) like the Darebee Stretching Workouts we put together (you can search the site for more).

Studies show that there is no evidence to suggest that pre-workout stretching reduces injuries, on the contrary they show that pre-workout stretching usually affects the ability of the muscles to give 100%. The same studies also show that post-workout stretching and stretching that is part of a separate workout routine deliver greater range of motion benefits and help increase muscle strength, speed and agility.

The bottom line is that stretching is definitely needed and it will always help you achieve more with your body but you should choose carefully when you do it and what type of stretching you do. You can always use a variety of stretching exercises rather than just stick to one particular type of stretching and you should always have some kind of stretching factored in, to maintain the health and elasticity of your muscles.

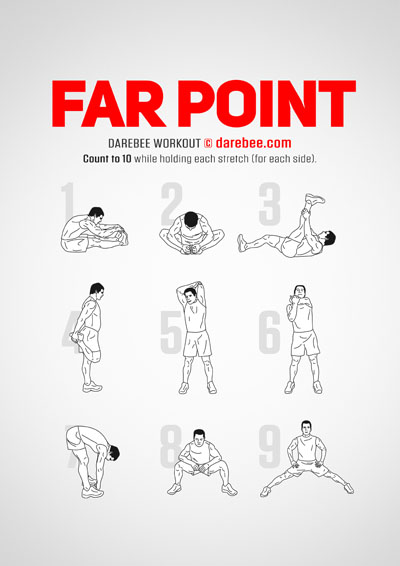

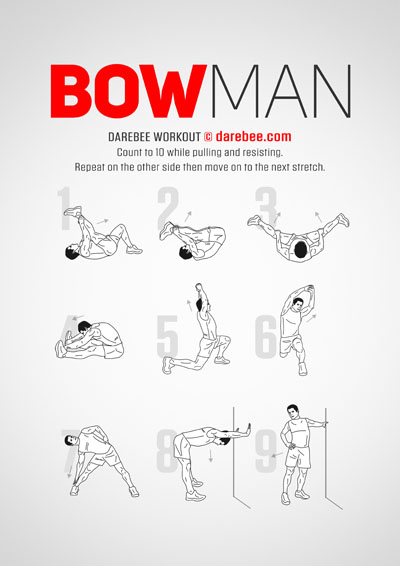

7 Stretching Workouts

Sources

1. Medicine ACoS ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7th ed. Baltimore: Lippincot Williams Wilkins; 2006

2. Page P, Frank CC, Lardner R. Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda Approach. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2010

3. McHugh MP, Cosgrave CH. To stretch or not to stretch: the role of stretching in injury prevention and performance. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. Apr 2010;20(2):169–181 [PubMed]

4. Sharman MJ, Cresswell AG, Riek S. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Sports Medicine. 2006; 36(11): 929-39.

5. Small K, Mc NL, Matthews M. A systematic review into the efficacy of static stretching as part of a warm-up for the prevention of exercise-related injury. Res Sports Med. Jul 2008;16(3):213–231 [PubMed]

6. Wicke J, Gainey K, and Figueroa M. A comparison of self-administered proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation to static stretching on range of motion and flexibility. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2014; 28(1): 168–172.

7. Willardson, JM. The application of training to failure in periodized multiple-set resistance exercise programs. J Strength Cond Res 21: 628–631, 2007

8. Vetter, R.E. (2007) Effects of six warm-up protocols on sprint and jump performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 21, 819-823.