When it comes to exercise there are two groups of people: those who love it and those who tolerate it. Both groups however struggle with time. In the modern world no one has enough of it and even those of us who love exercise because of the way it makes us feel struggle to find sufficient time to do it.

So, when a new study comes out that says that exercising on the weekend is enough, we all want to know if that is truly the case. Obviously, the findings are big news. There are a lot of people who fall into “the weekend warrior” category, i.e. people who don’t have time to exercise during the week but go flat-out on the weekend, and knowing whether that is good enough to sustain long-term physical health and cognition goals is really important.

The study[1] that was published in the Journal Of The American Medical Association, followed 350,978 adults (mean age 41.4 years; 50.8% women) from the US National Health Interview Survey without chronic illness over 10 years and used self-reporting to gauge the impact of exercise time and periodicity, against mortality rates from non-active groups of a similar demographic.

The study authors pointed out that when compared against their non-active counterparts, those who exercised on the weekend showed positive health trends with a reduction of early death from cardiovascular illnesses.

News organizations and even some health websites quickly picked up the results and published them under sensational “weekend warriors” type headlines that suggested that training on the weekends was just as good as training more regularly during the week provided the total number of minutes of suggested weekly activity were logged. This ranged from 240 minutes to 300 minutes in total.

A closer analysis of the study and its findings however reveals a much different picture. For a start the group of this study was compared to inactive counterparts versus other groups engaged in different formats of how they spread their exercise hours. The findings show that some exercise is preferable to none and that all exercise matters so, no arguments there. But there was no direct comparison with groups that were consistently active over more days of the week, nor was there an effort made to see if the “weekend warrior” lifestyle was consistently applied throughout the year.

The Benefits Of Consistent Exercise

Consistent, lifelong exercise is shown to help protect the body from some of the major chronic diseases commonly associated with the 21st century.[2] When exercise is part of our daily ritual “Large-scale studies indicate an almost linear relationship between increasing cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and longevity, with no signs of an upper limit.”[3]

There are three distinct factors that can act as obstacles that prevent us from engaging in consistent, lifelong, daily exercise: Available time, Injury and Motivation. In the next section we shall examine valid strategies you can use to overcome each one of them. Before we do however, it’s important to note that regular exercise not only activates the body and turns back our biological clock at a cellular level[4] but it also helps protect the brain from neuronal degeneration.[5]

Regular exercise changes the body’s physiology by gradually and consistently building up the pressure that activates the body’s adaptive response. It also changes the brain and body’s biochemistry. This leads to less anxiety and a reduction in the occurrence of depression. We become, in other words, more resilient not just on the outside but also on the inside. As a matter of fact, a 2021 study[6] showed that adults that were engaged in an active lifestyle had 60% less chance of developing anxiety disorders than their more sedentary counterparts.

Since the benefits of exercise are so significant it makes sense to learn how to apply consistent, viable strategies that help us exercise more. Just powering through because we know that exercise is good for us is not really an option. We can manage this for a short time but because we are forcing it, it becomes harder to sustain and it makes it more likely for our exercise plans to be derailed the moment something throws us off our schedule.

Remember the main obstacles to exercising sustainably, over time are: Available time, Injury and Motivation. As it happens inconsistent exercise patterns can result in quite serious injuries. This is because when we don’t exercise muscles experience de-strengthening[7] which severely affects their ability to perform at a specific, required level of intensity.

The link between this de-strengthening and injury rate, ironically enough, comes from “weekend warrior” studies[8] which show that the likelihood of severe injury from physical exercise increases significantly in the “weekend warrior” group when it’s compared to those who exercise a similar number of hours per week and at a similar intensity, but more regularly.

Injuries affect us both physically and psychologically and on their own can be quite demotivating when it comes to returning to exercise.[9] A willingness to somehow cram exercise when and where we can without a coherent plan and strategy to manage intensity and provide recovery can lead to us losing our way because of injuries and dropping out of exercise altogether.

Accumulated Exercise As Good As Continuous, Says Science

Accumulated exercise is exercise that is split over manageable chunks during the day or even during the week instead of being done in one continuous segment of time. Continuous exercise, as the name suggests, delivers extended bursts of activity over longer periods of time.

A study[10] showed that when it comes to health benefits; accumulated exercise, over time, delivers the same health results as continuous exercise. We have covered this in our guide to mini workouts and micro-fitness routines. It’s worth reiterating here because microworkouts can provide a really good solution to time-crunch problems.

The British Journal of Sports Medicine carried an analysis[11] of six studies of over 7738 participants aged 12–40 years which showed that a ten percent increase in strength resulted in as much as a four per cent decrease in injuries across the board.

Avoiding injury during training is as much the result of consistent training as it is of good preparation (i.e. a good warm-up, gradual increase in intensity, and so on). In that sense microworkouts provide a ready-made solution that allows for accumulated exercise to take place as well as controlled intensity.

Motivation

Motivation is, of course, the one thing we all struggle with and which we are never quite sure how to best tackle. Some think that you just need to “power through it” but that actually rarely works, especially when what you are looking for is the motivation to work out consistently as opposed to a one-off workout.

We have written on motivation, how to develop it and how to make it work for you before and you will find our science-backed article on it here. What we will say here is that motivation is dependent on your own personal goals and how you see yourself in the future. It has a strong emotional component[12] that affects our willingness to plan for something long-term. How you feel about what you do, how you feel about who you want to become and how you feel about why you are doing all that is critical to maintaining your fitness routine.

Strategies For Fitness Success

There is no “one size fits all” guide to fitness and motivation. You will always have to work out what makes things happen for yourself. However, on a general note it’s worth noting that if you go it all entirely on your own, at some point you will fail. Things will get too difficult, too crazy, life will happen, you will be at a really low point and all your carefully worked out plans will go out the window.

To avoid all this you will need to find your own cheerleaders. Your friends, your family, an online group or the Darebee Hive. You need to keep track of what you’re doing from one day to the next by keeping a log. Within The Hive logs make you publicly accountable, inspire others and often become the focus of conversations which help you to keep going in those moments when you falter.

If you’re not quite ready to be public about your training efforts then a private log you keep for yourself gives you a good idea of how you are doing and, provided you set some incremental, achievable targets, it can become a great motivator.

The ‘secret’ to getting fitter is to move your body more throughout the day. So on top of any structured exercise you set yourself to do you should find ways to increase the physical activity you do every day: walk to the local shops, take the stairs instead of the elevator, do some gardening, walk to a local friend’s house instead of driving, set time for a recreational walk. These are all small things that you barely notice when you do them but they all add up.

Summary

Obviously doing some exercise is better than doing no exercise at all. However, if you allocate all your exercise to the weekend hoping to make up for relative inactivity during the week you are putting your body under a lot of sudden physical stress and your mind under a lot of psychological pressure. The chances of things going wrong then increase significantly. A ‘bad’ weekend, a sudden injury, the accumulated pressure of the week, all can derail your health and fitness plans and it is these setbacks that often make us take a break and they then make it harder to get back to exercise, again.

It's way smarter to exercise throughout the week even if the intensity is not as high and add ‘hidden exercise’ activities such as shopping, cleaning, and doing housework. Incremental targets and constant activity take time to make themselves felt but they deliver results that are easier to sustain.

Some Suggestions For Fitness Plans and Workouts From Our Extensive Fitness Database:

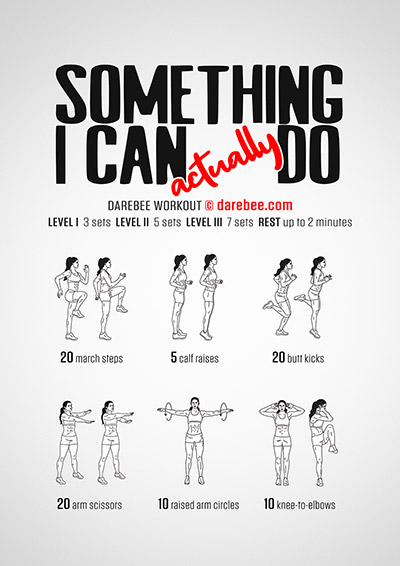

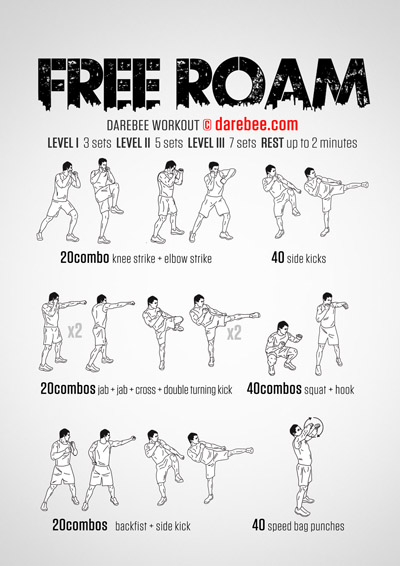

Avoid Injury by always working to your level:

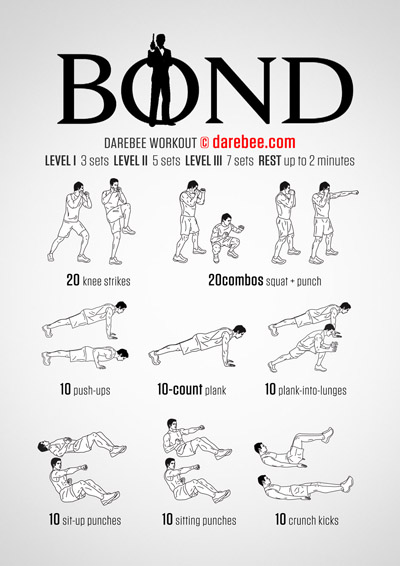

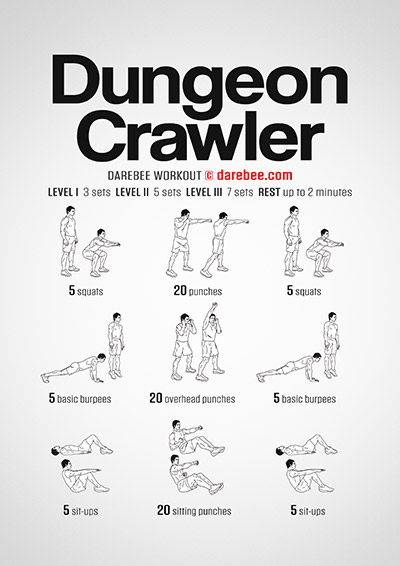

Stay motivated by not just exercising but by beating the bad guys, having the adventure of your life and saving the world with our RPG workouts:

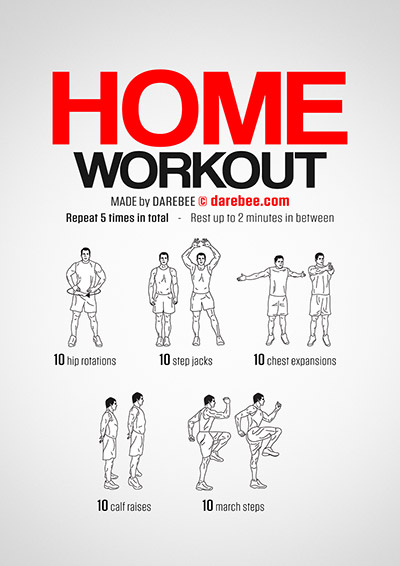

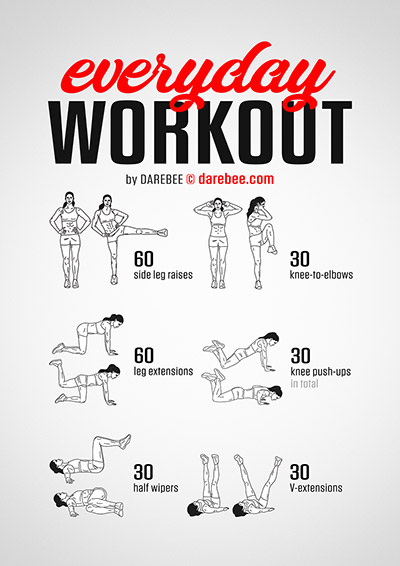

Save Time by ‘Exercise Snacking’ with microworkouts.

References

- dos Santos M, Ferrari G, Lee DH, et al. Association of the “Weekend Warrior” and Other Leisure-time Physical Activity Patterns With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Nationwide Cohort Study. JAMA Intern Med. Published online July 05, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2488

- Ruegsegger GN, Booth FW. Health Benefits of Exercise. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Jul 2;8(7):a029694. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029694. PMID: 28507196; PMCID: PMC6027933.

- Burtscher J, Burtscher M. Run for your life: tweaking the weekly physical activity volume for longevity. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jul;54(13):759-760. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101350. Epub 2019 Oct 19. PMID: 31630092.

- Carapeto PV, Aguayo-Mazzucato C. Effects of exercise on cellular and tissue aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2021 May 13;13(10):14522-14543. doi: 10.18632/aging.203051. Epub 2021 May 13. PMID: 34001677; PMCID: PMC8202894. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202894/

- Burtscher J, Millet GP, Place N, Kayser B, Zanou N. The Muscle-Brain Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Key Role of Mitochondria in Exercise-Induced Neuroprotection. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 17;22(12):6479. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126479. PMID: 34204228; PMCID: PMC8235687

- Svensson Martina, Brundin Lena, Erhardt Sophie, Hållmarker Ulf, James Stefan, Deierborg Tomas. Physical Activity Is Associated With Lower Long-Term Incidence of Anxiety in a Population-Based, Large-Scale Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12, 2021. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714014. ISSN: 1664-0640.

- Bogdanis GC. Effects of physical activity and inactivity on muscle fatigue. Front Physiol. 2012 May 18;3:142. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00142. PMID: 22629249; PMCID: PMC3355468.

- Roberts DJ, Ouellet JF, McBeth PB, Kirkpatrick AW, Dixon E, Ball CG. The "weekend warrior": fact or fiction for major trauma? Can J Surg. 2014 Jun;57(3):E62-8. doi: 10.1503/cjs.030812. PMID: 24869618; PMCID: PMC4035407.

- Jacob, Mathew & Jose, Joel Mathew. (2021). Consequences of injury and motivation to return to sports among athletes: a review literature. 2349-3429. 10.25215/0901.020.

- Murphy, M.H., Lahart, I., Carlin, A. et al. The Effects of Continuous Compared to Accumulated Exercise on Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Sports Med 49, 1585–1607 (2019).

- Lauersen JB, Andersen TE, Andersen LB Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:1557-1563.

- Berridge KC. Evolving Concepts of Emotion and Motivation. Front Psychol. 2018 Sep 7;9:1647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01647. PMID: 30245654; PMCID: PMC6137142.